Last spring, when my editor at Holiday House asked me how I

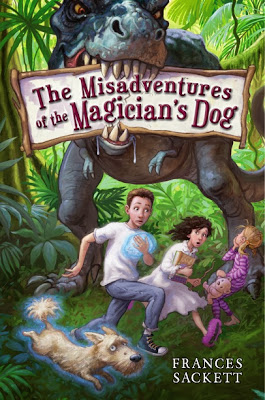

came to write The Misadventures of the

Magician’s Dog, I thought I knew how to answer. The seed of the novel dates back more than a

decade, to when a dear friend’s daughter adopted a dog named Anatole. He in no way lived up to his dignified

name: he was a scruffy mutt who liked to

jump the fence and frequently peed on the furniture. Still, he adored my friend’s daughter—which

became very important when she was diagnosed with juvenile diabetes at the age

of five. At a moment when her life was

falling apart, he was a best friend who never left her side. Perhaps for that reason, when she asked me

where Anatole lived before he came to her, I explained that he used to belong

to a magician and that he could talk and do magic. After all, isn’t there something magic about

a dog who can make a child feel that loved?

For years after that, I thought about writing a novel about

a dog who used to belong to a magician. But I couldn’t quite figure out

the rest of the novel—who would adopt the dog and what would happen

next. And then our country went to war, and I couldn’t stop thinking

about the kids of deployed service people: it seemed to me that these

children were carrying an enormous burden, one that they hadn’t chosen and that

my own children and their friends knew nothing about. So I wrote the

story of Peter Lubinsky, the son of a deployed air force pilot who adopts a dog

that used to belong to a magician. The

dog offers to teach Peter magic so that he can bring his father home—but only

if Peter first helps the dog rescue his former master, who has accidentally

turned himself into a rock.

This is what I told my editor when she asked about the

origins of my book. However, in

reflecting back, I think my answer only skims the surface of why I wrote this

particular story—just like most answers to the question of where stories come

from only skim the surface. We write the

books we write because of who we are in our deepest cores, because of the

questions that drive us, the desires we haven’t resolved. These are hard issues to talk about—at least

for me!—but I think there’s value in understanding a story’s unconscious

undercurrents. So I thought I’d use this blog post to try to examine some of

the deeper reasons I wrote the novel I wrote.

In my case, one of my obsessions is the complex nature of

love, with all of the push and pull of emotion that accompanies it. Love isn’t black and white: it’s full of ambivalence, one moment a source

of happiness and well-being; the next, of frustration, anger, hurt. This is true, I think, regardless of age—but

for children in particular, this sort of ambivalence can be very difficult to deal

with. Children whose parents are deployed

have more reasons than most to struggle with conflicting emotions. On one hand, they may adore and even idolize

their parents. On the other, they may

also feel fear, betrayal, and anger too at their parents for being gone. That’s a lot for any child to carry. Peter’s father is in a wonderful and loving

man, and yet he’s also left his children and put himself at risk. All Peter wants is for his father to come

home—but his father would have to be a different person in order to return.

I’m also obsessed with how anger affects people. When the dog in my book teaches Peter how to

do magic, he tells Peter that power is channeled through strong negative

emotions, like anger—and the more magic Peter does, the more angry (and evil!) he’ll

become. When a friend read the first

few chapters of an early draft, he wondered if magic done through anger might

be too dark for a middle grade novel.

But every instinct in me recoiled from changing this particular aspect

of the story. As every parent can

attest, anger is a powerful—and often scary—emotion for kids. I wanted to write about how anger that isn’t acknowledged

can fester, changing everything about how one sees the world. Yet I didn’t want

to say anger is “bad.” In the course of

my story, Peter struggles to acknowledge and make peace the anger he feels, to

understand that he can be angry with his father and still love him deeply. This, to me, is the emotional heart of my

story, the part of it that matters.

Of course, in writing about Peter’s attempts to reconcile

his conflicting emotions about his father, I was really writing about my own

struggles to understand love, anger, and the places where those two meet. I didn’t know this when I wrote my initial

draft, but I came to understand it as I revised. And I think that this understanding helped me

to make the choices I needed to make as a writer.

So here’s my advice for writers who are beginning the process of trying to tell their stories. Write something that excites you: whatever sort of story it is, just make sure it will keep you glued to your laptop, pouring the pages out. Have fun, and let your imagination run wild. But when you revise, go back and find the

emotions that are driving your story—the undercurrents that caused you to write

this book and no other. Once you

understand your story’s heart, polish it.

Refine it. Make it true.

Your story’s emotional core may not take up much space in terms of the

words in your book, which could be about dinosaurs and talking mice and crazy

carnivals (mine is). But make sure that

the words, no matter how few, are right.

And then send your story out into the world, knowing that it

carries with it a little bit of your soul.