|

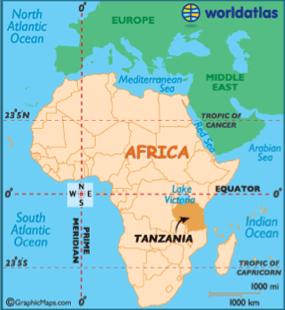

| Tanzania's there in dark orange--just below the equator. |

On paper, my job was to teach writing and English to journalism

students at a newly-formed university. The reality was that I did a little bit of teaching and a lot of learning during those two years. I was schooled in the many arts of basic living: washing clothes by hand, carrying water in a bucket on my head, and pounding rice in a giant mortar and pestle.

|

| Me pounding rice. Yes, I know the glasses look a little silly--it was the 1990s. |

I learned what it felt like to have malaria, typhoid and ecoli, and to value life in a place where almost everyone I knew had lost a sibling during childhood to a tropical disease. The most enjoyable lesson came in the form of informal, daily Swahili tutorials on my front porch with Tanzanian kids who congregated to play in the shade of a nearby flamboyant tree.

Within a few months I grew particularly close to one such

kid. Like many Tanzanians, Modesta didn’t know her age, but she was probably

about twelve when I met her. Every day after school, she scaled papaya and mango

trees and sold fruit door to door to help out her mom.

|

| Modesta in 1999. |

Modesta wasn’t afraid to

correct my Swahili, and her laughter filled my home. We started spending so much time together, villagers called me “Mama Modesta,” or Modesta’s

mother.

The only problem was my visa ran out after two short years. I had to leave Tanzania and, worse, Modesta. She was just graduating from primary school and, because her family was poor, early marriage was a more likely prospect than continued education. As a result, Modesta and I found a private boarding school for her to

attend and I arranged to pay for her school fees, but I still moved away broken hearted.

|

| A picture of Modesta a friend gave me on the day I left Tanzania. |

That first year back in the U.S., I spent

evenings after work reading and writing about life in Tanzania. A couple themes emerged.

Modesta, of course, was primary in my mind. I also thought about the unique resilience

of the women and girls I met in Tanzania: burdened with hours of house chores,

girls sacrificed sleep to study by kerosene lanterns at night; female students at my

university courageously banded together and wrote a letter condemning the behavior of a male

lecturer who had threatened to fail them unless they slept with him; Modesta’s

older sisters dodged marriage proposals so they could continue to work and control

their own finances to pay for their younger sisters’ education; and students of

mine wrote articles questioning the commonly-held, local belief that poor

widows were prone to witchcraft and responsible for societal woes. The

determination of these women and girls to improve their quality of life was inspiring.

|

| One of the many hard-working girls I met in Tanzania. |

That first year back, I also did a lot of reading about Tanzania's founding father, Julius Nyerere. The list of corrupt rulers African countries have suffered under is long, but

Nyerere’s name belongs on an entirely different list: that of the truly

principled. He increased literacy and life expectancy rates in his country; he

gave Tanzania a sense of national, rather than tribal, identity (no small feat

when you consider its many neighbors who have suffered civil war or conflict

between tribes); he attempted bringing his own brand of African socialism to

his citizens; and when he retired, he moved back to his rural village to farm,

occasionally taking trips to broker major peace deals.

|

| Nyerere in his home village. |

Without realizing it, I was carving out the components of a

book: a story set in historic Tanzania during the early presidency of Nyerere about a

strong Tanzanian girl, who would face some prejudice but who, through sheer

resilience, would not only prevail but would ultimately empower her village by

empowering herself. That’s the essence of A Girl Called Problem.

Oh, and for the real and far more important story, if you

are wondering about Modesta, she’s thriving. Modesta went on to spend high school

at an international school in India where my husband and I taught.

|

| Me and Modesta in India--note the glasses upgrade. |

After that,

she did a gap year volunteering in Tanzania, completed a university degree in

Uganda, and now works for an awesome organization called Media for Development International,

which makes popular television shows and movies with imbedded development

messages, like how to prevent malaria. Modesta has also helped out a lot with my book, providing research support, photographs for the glossary, and footage for this video supplement we made to go with the book.

Naturally,

A Girl Called Problem is dedicated to Modesta. Thanks for reading. If you'd like to learn more about the book, please visit katie-quirk.com.